About Bameno

Bameno is an Indigenous Baihuaeri Waorani community. The Baihuaeri Waorani People of Bameno are hunters and gatherers who have lived in the Amazon Rainforest since before written history. Their ancestral territory includes vast lands in the area now known as Yasuni National Park and Biosphere Reserve, in Ecuador. Yasuni is world-renowned for carbon-rich forests and extraordinary biological diversity, and is one of the last refuges for jaguars, harpy eagles, tapirs, giant otters, short-eared dogs, scarlet macaws and other threatened and endangered rainforest species.

The Waorani Peoples are legendary, even among other Indigenous Peoples in Ecuador’s Amazon region, for their extensive knowledge about the rainforest and its diverse plant and animal life. They are also famous for their hunting skills and long spears and blowguns. For centuries, Baihuaeri Waorani warriors, renowned and feared for their strength and ferocity, defended Yasuni from intrusions by outsiders who sought to exploit the forest and conquer its inhabitants. Now, the Baihuaeri Waorani of Bameno – a recently-contacted Original Indigenous People of Yasuni – must find new ways to protect Ome, the rainforest-territory that is their home and source of life. Bameno Community Tours is central to their remarkable initiative to conserve their rainforest home by ensuring economic independence and sustainable alternatives to oil extraction, logging and mining.

The first wave of peaceful, sustained contacts between Waorani and outsiders began in 1958, when evangelical missionaries from the U.S.-based Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) convinced Dayuma, a woman from another Waorani family group who was living as a slave on a hacienda, to return to her family’s ancestral territory and help the missionaries relocate her relatives into a permanent settlement and convert them to Christianity. The Waorani Peoples speak the same language (with some variations in speed and vocabulary) and share many traditions, but their social and political organization is based on extended family groups, or peoples, called nanicabo, who have their own specific ancestral territories and the right to territorial and political autonomy.

In 1967, the U.S.-based oil company Texaco (now part of Chevron) discovered oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon, near Waorani territories. As Texaco expanded its operations deeper into the forest, Waorani warriors tried to drive off the oil invaders with hardwood spears. The Baihuaeri Waorani and other Waorani who lived in the areas where Texaco wanted to operate had no contact with the outside world, so Texaco and Ecuador’s government asked the missionaries to extend and accelerate their campaign to contact, relocate and pacify the Waorani Peoples.

Using aircraft supplied by Texaco, missionaries searched for Waorani homes, and pressured and tricked Waorani families to move away from the paths of the oil crews. The Waorani who went to live with Dayuma and the missionaries were told that Waorani culture is sinful and savage, and pressured to change and abandon their traditions and way of life. Among other hardships, they suffered from severe culture shock and stress, as well as epidemics of new diseases that sickened, and even killed, family members. Large areas of the rainforest that had been their home were invaded and degraded by outsiders. In addition to oil infrastructure (wells, platforms, pipelines, waste pits and production stations), Texaco built a road into Waorani territories, and settlers used the road to colonize ancestral Waorani lands.

The Baihuaeri Waorani of Bameno were one of the last Waorani Peoples to be reached by the missionaries. Some Baihuaeri, not knowing what would happen as a result of “contact”, went to live temporarily with the missionaries but later returned to their ancestral territory. Others refused to leave. At least three Waorani Peoples still live in voluntary isolation in the forest, but two of them, the Tagaeri and Taromenane, have been displaced from large areas of their ancestral territories by oil operations and colonists. If you travel to Bameno by canoe, you will pass through ancestral Tagaeri (and Imairi Waorani) lands on the road first built by Texaco, where the forest has been so degraded by contamination and deforestation that the Tagaeri can no longer live there. Chevron (Texaco) no longer operates in Ecuador, but its tragic legacy remains, and other companies continue to incrementally expand oil exploration and production into new areas.

Today, the Waorani Peoples live in two worlds. Some ‘contacted’ Waorani have chosen to settle in towns such as Puyo, or near roads built by oil companies. But many Waorani – including the Baihuaeri Waorani of Bameno, other recently contacted Waorani who live in the area known as the Tagaeri-Taromenane Intangible Zone, and their uncontacted neighbors – still live deep in the forest, in harmony with the rainforest that gives them life and their way of life. Despite some rights and protections on paper, the forest and Waorani Peoples who call her Ome (territory) are still threatened by encroaching oil companies, colonists, and other extractive activities.

The Baihuaeri Waorani of Bameno are leading local efforts to defend the forest that remains in the area known as Yasuni from those threats, and their right to continue to live as Waorani in their ancestral homeland. They call themselves “Ome Gompote Kiwigimoni Huaorani (We Defend Our Huaorani Territory)”; for short, they say “Ome Yasuni.” Ome Yasuni is also defending the rights of the Waorani Peoples in voluntary isolation, and reaching out to neighboring contacted Waorani communities to build alliances to work together to protect as much forest as possible.

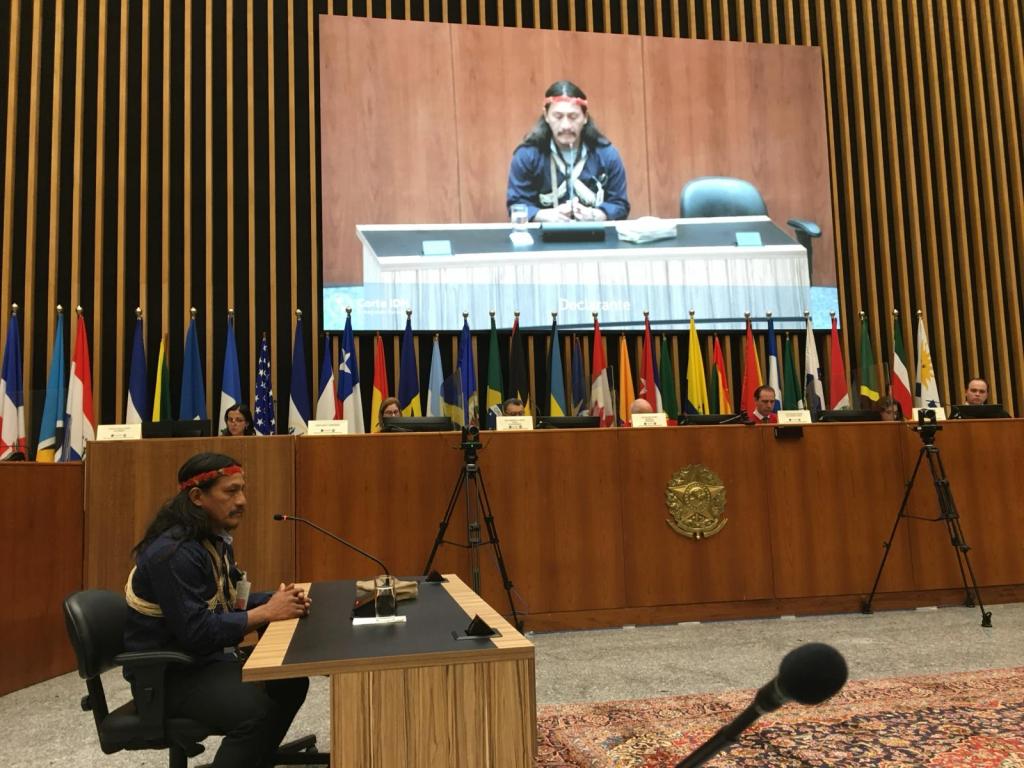

Penti Baihua, a traditional Baihuaeri leader and founder of Bameno Community Tours, has also testified to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in defense of his uncontacted neighbors, in the first international human rights case involving the rights of Indigenous Peoples living in voluntary isolation (Indigenous Tagaeri and Taromenane Peoples vs. Ecuador). The case, along with the defense of the forest and land and cultural rights by grassroots Waorani communities in Yasuni, offers a unique opportunity to protect the rainforest and make the promise of human rights a reality on the ground. Penti’s message to the governments and peoples who live where the oil companies come from is clear: “Territory is life; deje vivir, let us live.”

Growing research is proving that the best way to safeguard nature is to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their lands and territories. Secure land titles are an essential means to respect and protect those rights. As the Baihuaeri Waorani of Bameno defend the forest and demand legal recognition of grassroots territorial and cultural rights, they are also defending biodiversity and global climate.

A word of caution: If you search the internet or libraries looking for information, please keep in mind that there is a lot of confusion and mistaken information about the Waorani Peoples and Yasuni. Anthropology is not an exact science; anthropologists frequently base their interpretations on limited information, debate with each other, modify their interpretations over time, and are influenced by their own culture and way of thinking. Academics in other fields, reporters, documentary filmmakers, NGOs and governments also make mistakes, and frequently ignore grassroots voices. The resulting misinformation is all too often echoed or repeated by others.

We invite you to visit the Bameno Community Tours Learning Centre to learn more